Justice

VR Amendment

Electoral College

Congress 2005

Ohio 2004

Why it Matters

Voting History

Voting FAQ

Home

The Electoral College:

An Embarrassing Vestige of Slavery and Segregation

Unsavory origins of the electoral college

The Electoral College began as an awkward compromise, mainly to appease slave-holding states. Quoted from Ditch Rickety old Electoral College, (January 4, 2005 editoral in the Modesto Bee)

“The Electoral College was an anachronism from the beginning. It was a jerry-built contraption adopted because delegates at the 1787 Constitutional Convention couldn’t agree on a method to elect the president.”

“Those who opposed direct election said, “The people are uninformed, and would be misled by a few designing men.” Others thought the large size of the country “renders it impossible that the people can have the requisite capacity to judge of the respective pretensions of the Candidates…”

“The real sticking point against direct election came from Southern states who feared being at a disadvantage since part of their population, slaves, was forbidden from voting…”

“Deadlocked between direct election and election by Congress, the convention referred the issue to the Committee on Detail, which revived Wilson’s compromise proposal to have the president be “chosen by Electors to be chosen by the people of the several States.” That last-minute compromise was how the Electoral College was born. It clearly is an artifact produced by deadlock. It is not a venerable institution to be saved at all cost.” read more

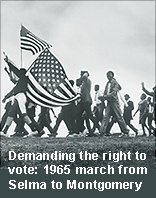

Fiercely defended by segregationists in 1969

Nearly abolished in 1969, the Electoral College was rescued from the dustbin of history only through the determined efforts of notorious segregationist Senators James Eastland of Mississippi and Strom Thurmond of South Carolina. In Peculiar Institution, which appeared in the Boston Globe on October 17, 2004, Prof. Alexander Keyssar of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government wrote:

“What was not discussed in the aftermath of the 2000 election was the little-known fact that the United States came very close to abolishing the Electoral College in the late 1960s. A constitutional amendment calling for direct popular election of the president was backed by the American Bar Association, the Chamber of Commerce, the AFL-CIO, the League of Women Voters, and a host of other un-fuzzy-minded pillars of civil society. On Sept. 18, 1969, the House of Representatives passed the amendment by a huge bipartisan vote of 338 to 70. President Nixon endorsed it, and prospects for passage in the Senate seemed reasonably good. A poll of state legislatures indicated that the amendment would likely be approved by the requisite three-quarters of the states.

“The effort ultimately failed — but not because of concerted opposition from the small states. In fact, many political leaders from small states supported the amendment. What blocked the reform movement was a more troublesome cleavage — one involving race and the political power of the South…

“Amendments calling for a direct popular vote had also been introduced as early as 1816, but for most of our history such proposals were doomed by a stark political reality: The South would never accept them. The issue was not small states versus big states but slavery and racial discrimination.

“Before the Civil War, the “three-fifths compromise” in the Constitution meant that slaves counted (as three-fifths of a person) towards a state’s representation in Congress and thus in the Electoral College. Had the president been elected by a popular vote, Southern influence would have shrunk sharply, limited to the number of votes actually cast.

“This system operated even more perniciously during the Jim Crow era (extending into the 1960s), when the white South benefited from what could be called the “five fifths” clause: African Americans counted fully towards representation in Congress and the Electoral College, but they still could not vote. The number of votes actually cast in the South between 1900 and 1960 was tiny in comparison to the size of its electoral vote. A popular election for president, thus, would have dramatically reduced the political power of the South while creating pressure for Southern states to expand the franchise…

“The Senate Judiciary Committee was chaired by James Eastland of Mississippi and counted Strom Thurmond among its members. Both men were die-hard segregationists who had voted against every civil-rights and voting-rights measure that had come before them. Neither wanted to have presidents elected by a national, popular vote.

“In 1969, the House of Representatives passed an amendment to abolish the Electoral College by a huge bipartisan vote of 338 to 70. President Nixon endorsed it, and prospects for passage in the Senate seemed reasonably good. A poll of state legislatures indicated that the amendment would likely be approved by the requisite three-quarters of the states.”

However, Senators Strom Thurmond (R-SC) and James Eastland (D-MS), die-hard segregationists who had voted against every civil-rights and voting-rights measure that had come before them, opposed having presidents elected by a national, popular vote, and fought fiercely to stall the measure for nearly a year, until support for it finally waned.” read more

Put your patriotism into action

YOU can help to change this!

- Contact your U.S. Representativeby email or by phone (202-224-3121)

and ask him or her to sponsor legislation to abolish the Electoral College. - Contact your two U.S. Senatorsby email or by phone (202-224-3121)

and ask them to introduce or co-sponsor a similar bill in the Senate!

Accountability

Greens support elections and governing processes that increase public participation. more

Green Officials

State and local Green officials serve across the U.S., from California and Colorado to Maine and Washington, D.C. more

Respect Diversity

Our political system should bring us together as one nation, not divide us against one another. more

Sustainable Future

Ending our fossil fuel dependency will help build a sustainable future for our children. more